The Box Man (2024) • Blu-ray [Third Window] — compelling philosophical ponderance of identity

A nameless man gives up his identity to live with a cardboard box over his head, meeting a range of people as he wanders through Tokyo.

The Box Man is making its Blu-ray debut from Japanese cinema specialists Third Window Films and, apart from a few well-received festival showings and arthouse screenings, this is effectively its first distribution beyond Japan. It’s an unconventional film in the tradition of the poetic and reality-rupturing To Sleep So As to Dream (1986) but with the added uneasy experimental edge of the likes of Tetsuo: Iron Man (1989) and even some of the offbeat tragicomedy of Big Man Japan (2007).

It will appeal to those who relish cinema as an engaging intellectual challenge, rather than passive ‘popcorn’ entertainment, or simply wish to surrender to its seductive, dreamlike weirdness for two hours. As the promotional tag line says, “anyone who is conscious of the Box Man will become a box man…” Although this is gender-specific throughout most of the movie, with the narrative following the entwined fates of three men who obsess about becoming the box man, more diversity creeps in towards the finale when it seems anyone can become a box person, including you. In fact, you may well already be one without realising it, on a metaphorical level at least.

Kōbō Abe’s experimental 1973 novel The Box Man / 箱男 was long thought to be unfilmable because it relies so much on literary trickery and individual reader experience. Since its publication, it’s been analysed extensively with the term ‘ontological’ often used to categorise it. If you just had to Google that word, then you may not be in the targeted demographic — if, indeed, there is one. I admit to not reading the book, though I have dipped into translated sections. The general impression is of a very clever and rather showy author who enjoys challenging their readers to an intellectual game rather than delivering a conventional story.

However, what’s even cleverer about director Gakuryū Ishii’s treatment is that he doesn’t even attempt to present a literal transcription, instead utilising the unique visual language of cinema in a way that’s almost directly analogous to the wordplay. The screen adaptation, while respecting the structure of the source material, deliberately transposes the exploration of relationships between author and reader into those between director and viewer. Cinema is a vastly different medium to literature and The Box Man is among very few movies based on books that embrace those differences so consciously and effectively.

Not only was the author, Kōbō Abe, a novelist, but also a medic, political activist, and multidisciplinary artist. He wrote and directed for the stage, often designing the productions with his wife and creative collaborator, Machi. He was a fine art photographer, exhibiting his work in galleries as well as integrating them with text. In The Box Man novel, he deploys street photography alongside incongruous captions that inform, imply, or present tangential readings of passages from the main body of the book, thus adding additional enigma and ambiguity. Abe also understood how text and image could complement or contradict each other.

After abstract images that suggest cosmic starscapes morph into a single, screen-filling monochromatic eye, the movie opens with a montage of Abe’s photographs and newspaper clippings that evoke the Japan of the early-1970s, the period setting of the novel. One headline proclaims, ‘Japan stagnates,’ another laments the increase in gun crime, while another notes the nation’s transition, ‘from economic to information society.’ The cosmic imagery followed by gritty, sometimes indistinct, photography set to the excellent, bass-led jazz score by Michiaki Katsumoto creates a dreamy Lynchian atmosphere. There’s also an overly serious voiceover that introduces the enigma of the Box Man who seeks anonymity and solitude and must accept the ever-present possibility of death when no one would notice nor care.

We then meet our first Box Man (Masatoshi Nagase). As the black and white photographs come to life and colour seeps into the images, we notice that we have been brought up-to-date and are no longer in the ’70s because the societal issues that Kōbō Abe examined in his novel remain relevant, with some exacerbated. One such theme is the isolation of the individual, and it has become a broader concern in 21st-century Japan as more people, predominantly young adults, choose to withdraw from society. This elective isolation is referred to as hikikomori, with some choosing as complete a break from social contact as possible. Others may observe the outside world and interact only via screens.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us sampled what it’s like to be hikikomori, isolated in our boxes, viewing the world and each other only through digital peepholes. Of course, the same metaphor could have been applied to the psycho-social state of a nation still searching for its post-war identity in the 1960s and early-’70s while feeling robbed of power as an observer of change, first under the governance of the US, and then by its capitalist ideals. Or, looking even further back, perhaps a critique of the sakoku period of the 18th and 19th-centuries, when Japan closed its borders and isolated itself from the rest of the world during the Edo era.

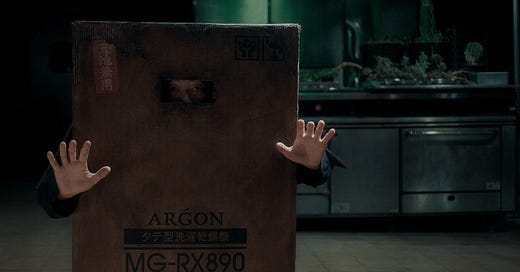

Here we have a man living in a box, living in a cardboard box. Just like a down-and-out using a big box for shelter, he’s able to hide in plain sight on the streets and observe the passer-by who never notice him. Or if they do, they feign ignorance. The man inside the box shall remain nameless but he’s no ordinary hapless homeless person. In this case, it is a lifestyle choice.

The sturdy box is also extraordinary and has been tricked out in several ways. There’s a viewing portal and flaps to allow for arms to reach outside the box. A small hole turns the inside into a camera obscura projection booth, and there are numerous clips and shelves to accommodate darkroom facilities and keep his notebooks secure. For it’s the mission of the box man to relinquish his past life and identity, remaining always isolated inside the box, from where he can observe and document society unilaterally, without ever being a part of it.

However, there are those who covet the box and are not prepared to leave him in peace. During the first act, he endures two attacks that are both comedic and concerning. Firstly, by an assassin (Kiyohiko Shibukawa) wielding a vicious-looking lance and wearing a patchwork of rags as camouflage. Secondly, by a gun-toting masked man clad in SWAT gear who manages to injure the Box Man seriously enough to require medical attention… By the time he wakes up in hospital, and no longer in his box, we’ve completely bought into a skewed version of reality.

The hospital turns out to be a private lab hidden away in a secret warehouse where an ex-military doctor referred to as the ‘general’ (Kôichi Satô) continues his wartime research into cacti and exotic plants, with specimens kept in their own environmentally controlled vivaria.

Now, as this is basically the film’s first run outside Japan, I’ll avoid giving too much away. Suffice to say that the narrative, although ponderous at times, is never boring and develops in surprising, often absurd directions. We learn that the general is terminally ill because of some past experimental misadventure. He wants to assume the Box Man’s identity, or lack thereof, to commit a “perfect crime,” assisted by a ‘doctor’ (Tadanobu Asano) and Yoko (Ayana Shiramoto) who sometimes role-plays a nurse. She’s the only named character and cryptically asks the man who was inside the box to save her.

With the addition of a detective (Yūko Nakamura) ostensibly investigating the fake doctor, that’s the entire principal cast. Luckily, they’re all superb and eminently watchable, despite dealing with some difficult material, and entirely convincing, even when they’re unbelievable.

Masatoshi Nagase and Tadanobu Asano are seasoned actors who have repeatedly starred together in a few outrageous movies directed by Gakuryū Ishii — notably Electric Dragon 80,000V (2001) and Punk Samurai (2018), which are also available from Third Window Films. They’re both fearless actors who relish varied and challenging roles which they tend to play with great depth and humanity.

Tadanobu Asano is probably better known outside Japan after his major recurring role as Lord Yabushige in the FX television miniseries (2024). His most recent screen appearance was in a cinematic music video for extreme J-Rockers Deviloof’s Inshu / 因习 (2025) in which he portrays a version of the well-known character of Iemon Tamiya in a reworking of the seminal Japanese ghost story Yotsuya Kaidan / 四谷怪談 aka The Tale of Oiwa’s Ghost.

Kôichi Satô is a hard-working character actor who has also starred as Iemon Tamiya, in Kinji Fukasaku’s reworking of the same story as Crest of Betrayal (1994). In The Box Man he exudes ennui and a nonchalant, manipulative malevolence in executing a complex plan that seems to hinge on some philosophical notion that a loss of self is a way to defeat the tyranny of death. Or something along those lines. He’s a sick man basically housebound in his warehouse lair and there are clear parallels of living inside a box-like space, viewing the world through the portals of CCTV and screens. Nevertheless, he seems to hold power over others, especially Yoko whom he uses for his own pervy pleasure and as a lure for others.

Although in her early twenties, Ayana Shiramoto already has a significant screen career, having landed her first credited role aged nine. She was a familiar child star in Japan best known for her role as Iyu in Kamen Rider Amazons (2016–17) TV series and follow-up movie, Kamen Rider Amazons: Reincarnation (2018). The domestic press made much of The Box Man being her breakthrough adult role and she’s excellent as Yoko, relying as much on silences and expressive nuances as on her minimal dialogue. She has such beauty and poise that her nude scenes rapidly become uncomfortable viewing as she performs lewd acts, administering recreational enemas, and talking dirty while being fervently snuffled.

These scenes emphasise the voyeuristic nature of cinema as we watch through the portal of the screen just as the Box Man watches through the slot in his box. We can only observe, we can’t feel — or smell — the action and are powerless to intervene. We are simply anonymous observers… forced to rely on our fictional proxy to ‘save’ her. Yet there are a few more narrative detours before we reach a dénouement which might not deliver the desired outcome.

The ending was a somewhat inevitable punchline but, for me, it was a little too on the nose. I would have been just as happy with a more elusive and understated conclusion, but that’s a minor quibble and overall, I applaud Gakuryū Ishii’s filming of the unfilmable and commend Kōbō Abe’s choice of director and the director’s subsequent choice of cast…

Although the novel was inescapably text-bound, despite the occasional use of photographs, Kōbō Abe understood the moving image and had written and directed two short art films of his own as well as writing original screenplays for others. He famously collaborated with the director Hiroshi Teshigahara on the short film Ako / あこ (1964) and four feature film adaptations of his novels, Pitfall / おとし穴 (1962), the internationally acclaimed Woman in the Dunes / 砂の女 (1964), The Face of Another / 他人の顔 (1966), and Man Without a Map / 燃えつきた地図 (1968). Shortly before his unexpected death, in 1993, he’d met Gakuryū Ishii to discuss filming The Box Man.

So, it could be said the movie was more than 30 years in the making. By 1997, cast and crew were assembled but the day before shooting was to commence, the funding fell through and, much to Gakuryū Ishii’s frustration, the production was cancelled. Now, this may have been a blessing in disguise because Ishii describes his original treatment as being a fusion of Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati with musical numbers. Over the intervening quarter century, the maturing and increasingly experienced director had an entirely new script co-written with Kiyotaka Inagaki that he aptly summarises as a slapstick and offbeat philosophical horror movie. Incidentally, the original cast back in 1997 included Masatoshi Nagase for the lead role along with Kôichi Satô as the general. Finally, they were able to reprise their roles and, fittingly, the film premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2024, which also marked the 100th anniversary of Kōbō Abe’s birth.

JAPAN | 2024 | 120 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE • COLOUR | JAPANESE

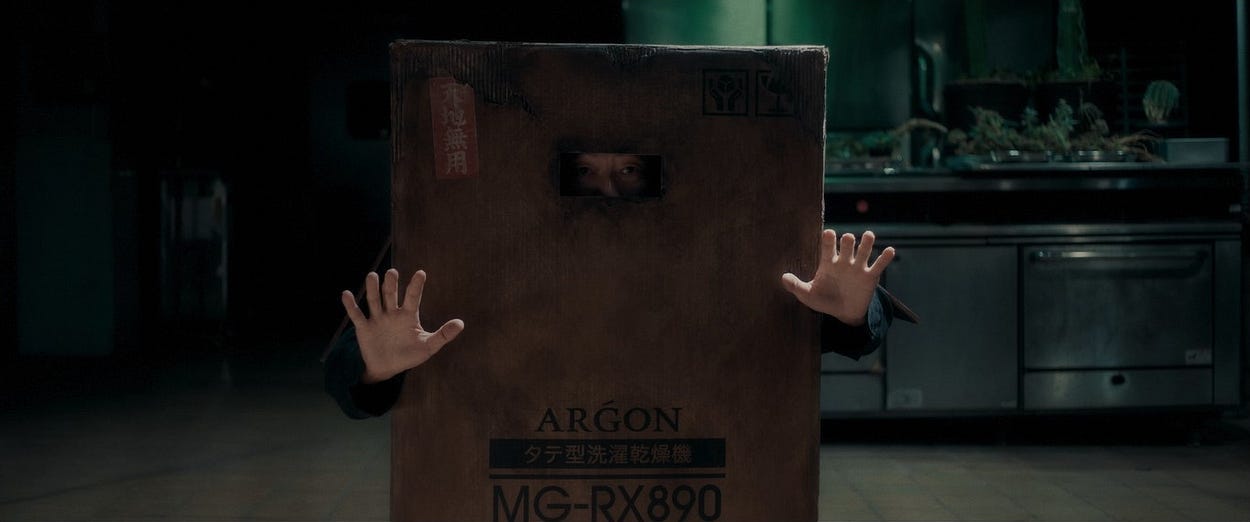

‘Slipcase Edition’ Blu-ray Special Features:

Special ‘The Box’ Slipcase Edition (Limited to 2000 copies). A desirable box, but no sign of a collectors booklet? A missed opportunity that should be prerequisite for any physical media release.

Feature length audio commentary by Tom Mes. He begins by placing the film in the context of Gakuryū Ishii’s career before turning his attention to the source material and discussing the socio-political climate of Japan in the 1960s and early 1970s, when Kōbō Abe was writing the novel and the nation was still dealing with the literal and metaphorical fallout of war and the ensuing US occupation. He contrasts the optimism of the influential 1970 Osaka World Expo with the civil unrest known as the Anpo Protests that same year, the Asama-Sansō incident when United Red Army radicals took hostages at a ski lodge in a 10-day standoff with police, and the global oil crisis of 1973. This problematic period caused people to question society and search for new values and ways of living. He gives a good chronology of the production process, from the abortive production in the 1990s to the successful version we’re watching together, then talks about thematic overlaps found in Ishii’s other films. There are the expected backgrounds for the cast before he allows some tangential meanderings about the history and development of cardboard and how it replaced wooden packing crates and was used to stiffen top hats. He also tells us about factory otaku culture that fetishises industrial architecture. Along the way, he shares his personal responses to the film’s content, which are always interesting regardless of whether one concurs or not.

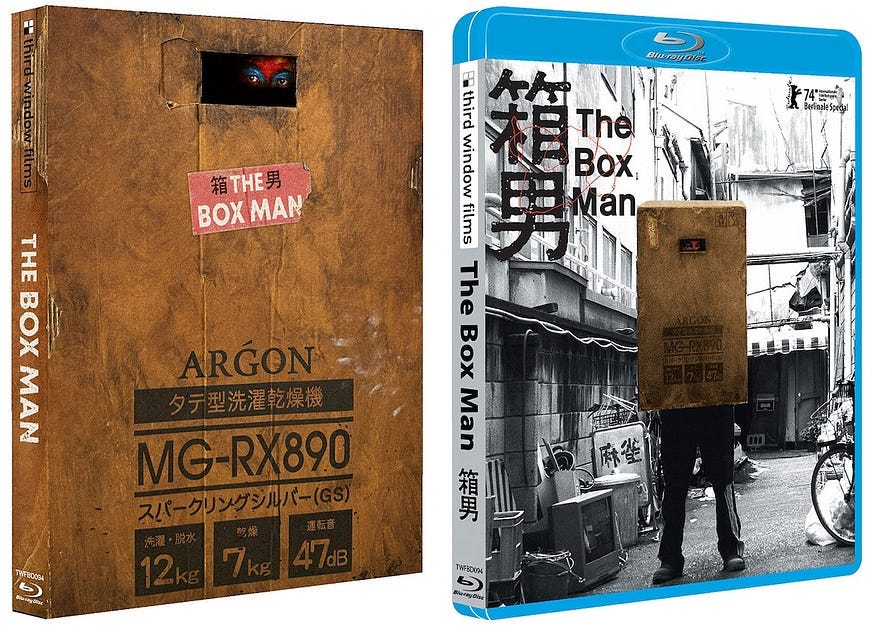

27-minute Director Q&A at the Japan Society. In which Gakuryū Ishii recalls meeting with Kōbō Abe and talks quite openly about his conceptual approach to the text as metafiction and his attempt to make a meta-film where the viewer becomes the Box Man just as when reading the book the reader is absorbed into becoming the protagonist in their imagination.

24-minute Director and Cast talk event. Gakuryū Ishii, Masatoshi Nagase, Tadanobu Asano, Kôichi Satô, and Ayana Shiramoto demonstrate the same dark deadpan humour that we see in the film and those who were involved with the cancelled production in 1997 reminisce about their time preparing to film in Germany and how mortified Ishii had been when the news of the funding failure reached them. They then discuss their experience making the film with a few entertaining anecdotes about their team dynamics.

Cast comments from inside the Box.

Trailers.

Cast & Crew

director: Gakuryū Ishii.

writers: Kiyotaka Inagaki & Gakuryū Ishii (based on the novel by Kōbō Abe).

starring: Masatoshi Nagase, Tadanobu Asano, Kôichi Satô & Ayana Shiramoto.

Originally published at https://www.framerated.co.uk on June 28, 2025. All images are used according to the Fair Use doctrine in US & UK law for review, commentary, and education.