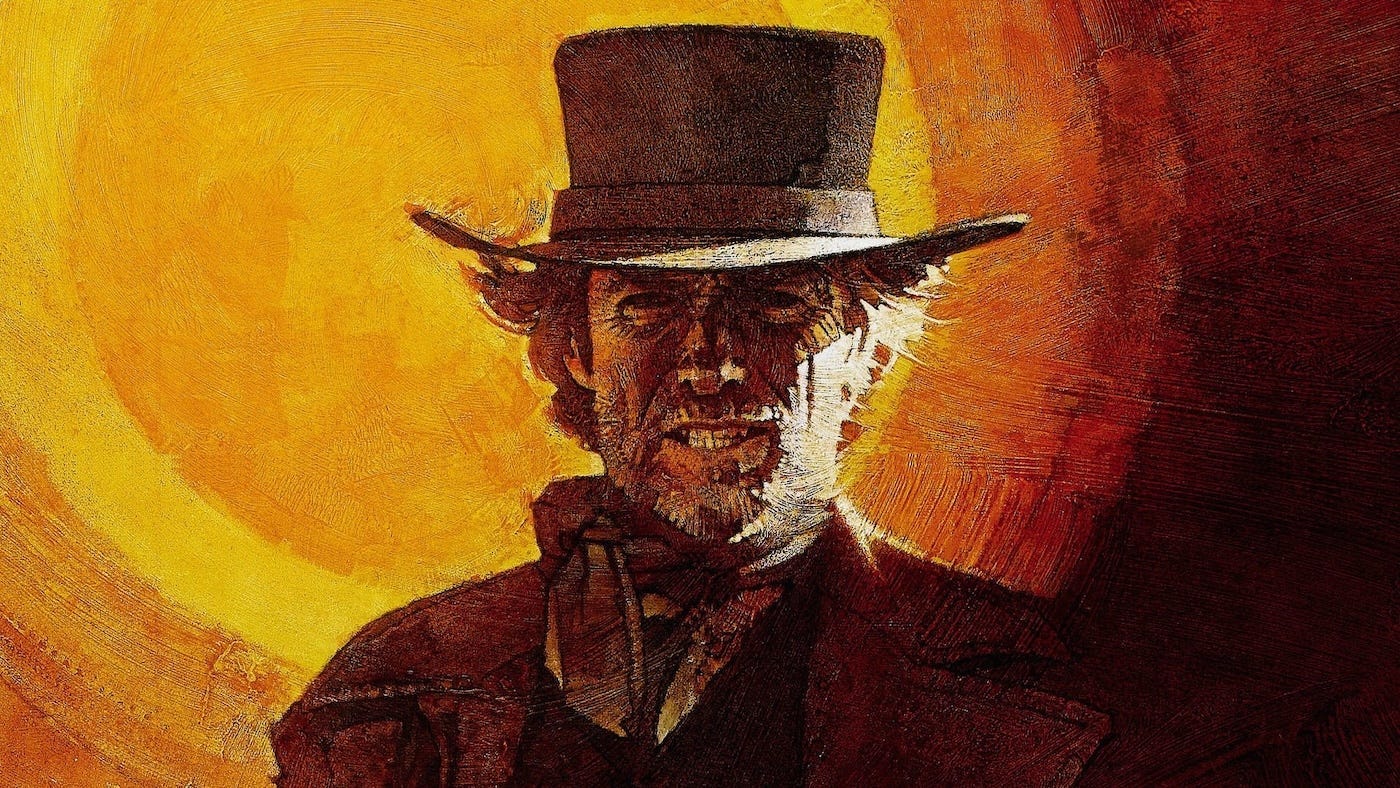

Pale Rider (1985) • 40 Years Later — Clint Eastwood’s middling return to the genre that brought him stardom

A mysterious preacher protects a humble prospector village from a greedy mining company trying to encroach on their land.

Just over two decades after gaining international recognition and widespread acclaim for his roles in Westerns, Clint Eastwood returned to the genre in Pale Rider. It was the only Western he starred in during this decade, as well as the most popular genre entry in the 1980s. Unlike the Spaghetti Westerns that cemented the actor’s depictions of rugged, mysterious outsiders, Eastwood directed this film, a move that, in spite of his directorial talents in other films, only winds up making one nostalgic for what was at that point a bygone era in the Western genre.

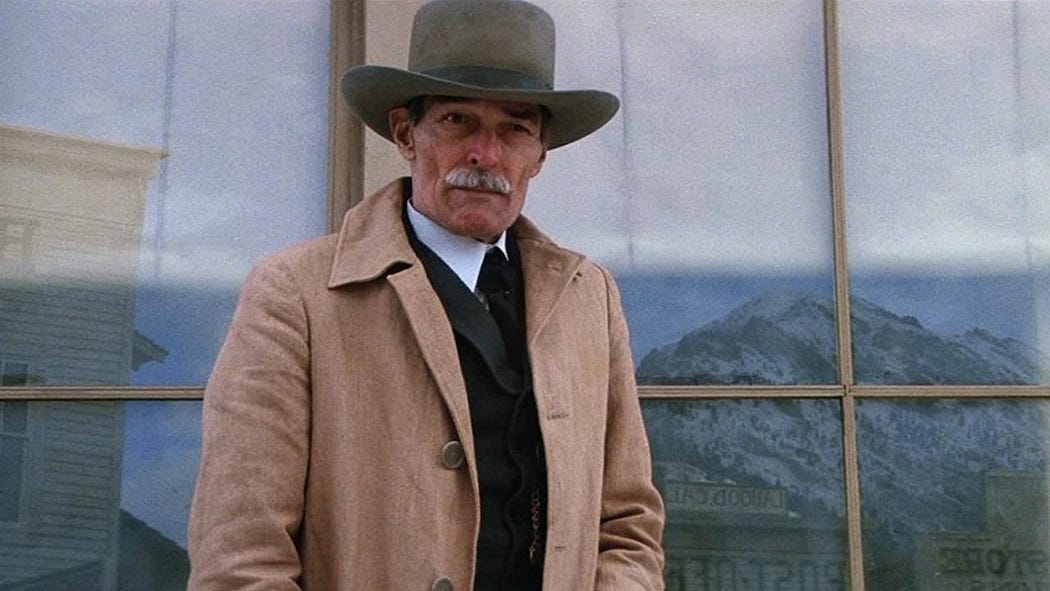

Despite the actor-director’s versatility, he’s no Sergio Leone, with Pale Rider betraying this from its very first scene. It sets up a thunderous showdown in a rural area, interspersing an incoming cavalry with the much gentler rhythms of everyday life in the home of Hull Barrett (Michael Moriarty), his girlfriend Sarah Wheeler (Carrie Snodgress), and Sarah’s teenage daughter Megan (Sydney Penny). Hull is a decent man, but he’s nowhere near tough enough to take on the violent henchmen of brutish mining baron Coy LaHood (Richard Dysart). So when these men do arrive, he is powerless to stop them, a scene communicated so often through close-up shots of each character that the chaos which unfurls feels manufactured.

Close-ups and reaction shots were used superbly by Leone, so it’s only right that Eastwood would employ them regularly in his directorial interpretation of the genre, where expressions and eyes do as much talking as words can. But the scene has the unfortunate effect of making these characters feel as if they’re responding to one another in completely different environments, with each reaction shots feeling at least a second too late in response to the interaction that provoked them into being. Worse still, their repetitive pattern drills a rote visual formula into viewers. First Hull watches the action that just occurred, or the event currently unfolding, then Sarah, then Megan, and before the compilation has reached its close you’re left wondering whether these reaction shots will ever be able to avoid being outpaced by Pale Rider’s action.

It’s a losing battle, especially when each character is so displaced from one another that it’s not just that the scene lacks urgency; it doesn’t even seem like anything is befalling them. It’s as if each member of this ensemble is thrown into a new reality every few seconds, where the terrible forces of LaHood’s men home in on them (and only them), then chuck them back into the real world again and warp reality for their next victim.

What is most interesting about the way action is composed in this film is how it makes itself near impossible to parody. Pale Rider takes itself seriously, too seriously for how weightless some of these scenes come across, but it’s rather humorous all the same. If one were to satirise Pale Rider, a formula would not need to be devised to do so; it is already baked into the film’s DNA. You would only need to depict near-identical shots to the ones already framed in this film, but with absurd reactions from characters to highlight the awkwardness of a movie that refuses to unfold naturally. It is so compartmentalised that it’s as if a cog is being turned at the arrival of a new shot, even in relatively fun action scenes where the mysterious outsider, only known as The Preacher (Clint Eastwood), effortlessly beats up LaHood’s henchmen.

In his grand entrance into Hull’s life, The Preacher beats up four men with ease, sending their guns and other weapons sailing through the air, appear to spin ad infinitum as they rise ever higher. These are shot selections that feel tailor-made for comedy, especially when the film returns to the same object, still spinning in mid-air, but alas, such humour is never intentional. In typical fashion of brainless, grunt henchmen in genre film, none of these men ever think to use their strength in numbers to attack this mysterious badass all at once, instead allowing The Preacher to fight them one at a time, offering neither this elusive protagonist or the viewer room to believe that he won’t succeed handily.

This makes for a series of action scenes that are frequently enjoyable (and not always intentionally), but never truly immersive. Much like this film, there’s always something to appreciate, whether that’s in the form of a performance, an enjoyable plot beat, or a picturesque shot of distant hills and valleys, but it feels like the work of someone whose glory days are behind them. Perhaps it’s not Eastwood that has lost his touch — his later acting and directing work refutes this claim easily — but the Western genre itself. Pale Rider as a whole comes across as a last-gasp effort to revive something that had since gone out of fashion, its greatest proponents and creators having moved on, stopped working entirely, or passed away. Eastwood utilises his rugged masculinity as best he can, but that doesn’t mesh well with the soft-spoken man that endears himself to the film’s central family unit. He’s too many things at once, and all of them are so pure that the movie trips over itself to bless him with its reverence.

There are religious themes aplenty, usually with Megan as their mouthpiece, who struggles to believe in God given the woes that have befallen her and her family. This, paired with The Preacher possessing ethereal qualities that paint this drifter as a symbol of death (hence the movie’s title) lend some intrigue to their dynamic, but not enough to stir much feeling. This is a rather silly film that never seems able to recognise this quality within itself. Like with Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond, Pale Rider is hard not to pity, since its greatest failing is not that it is bereft of any semblance of style or quality, but that it is out of touch and unable to understand how to adapt to its surroundings (in this case, a film industry that left this genre to rust). It’s a stray tumbleweed drifting through an arid desert.

A conversation between Megan and The Preacher, where she attempts to seduce this mysterious figure before he lectures her on why she shouldn’t, is comprised of the kind of ham-fisted moralising that makes one appreciate the same qualities in American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman. That film was playing into its humour from the get-go, whereas Pale Rider strains to be a sincere and simplistic return to form for the Western genre. Miscalculated and out of touch, the film is anchored by its strong performances, even if it’s a reminder that not every trend, genre, or style of filmmaking should be revived. One is much better served rewatching one of the classics of the Western genre — such as the films that kickstarted Eastwood’s illustrious acting career — than experiencing the very mild thrills of Pale Rider.

USA | 1985 | 116 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Cast & Crew

director: Clint Eastwood.

writers: Michael Butler & Dennis Shryack.

starring: Clint Eastwood, Sydney Penny, Michael Moriarty, Richard Dysart, Carrie Snodgress, Chris Penn & John Russell.

Originally published at https://www.framerated.co.uk on June 25, 2025. All images are used according to the Fair Use doctrine in US & UK law for review, commentary, and education.