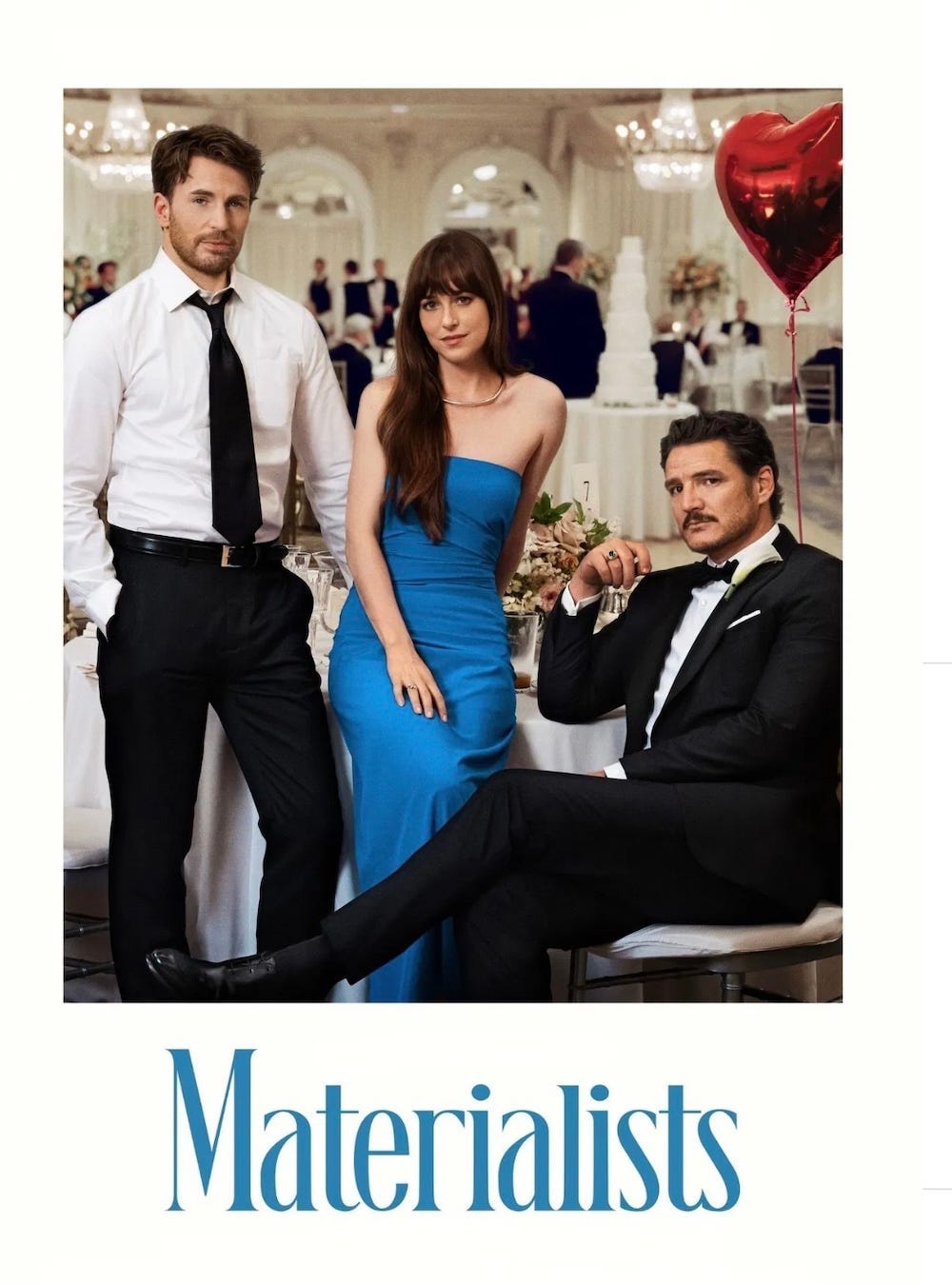

Materialists (2025) — romantic dating drama stumbles but delights

A young, ambitious New York City matchmaker finds herself torn between the perfect match and her imperfect ex.

All the bad things you’ve been hearing about Materialists were no lies, but despite the misgivings, I found it a true delight. The director, Celine Song, hasn’t shaken loose the odorous obviousness of middle-brow theatre (she was trained as a playwright), and was already embracing the adulterated simplicity of film with open arms. Past Lives (2023) got by with it because of its elegant construction and a personal subject treated to fine lyricism. It was like a play in motion, freed from the confines of the stage. In this new romantic dramedy, she no longer has the same control over her subject. The failings are conspicuous enough, and they belong more to the third-rate rom-coms of Fred Schepisi and Nicole Holofcener than the tediously self-conscious The Phoenician Scheme (2025) and so on. It’s a jolly good diversion if you’re willing to leave the flaws where they are.

The story was inspired by Song’s brief stint as a matchmaker, but she stretches it too thin to make it personal. It’s the good old American yarn (Road to Morocco, Sabrina, The Philadelphia Story) of a beautiful girl in the predicament of two beautiful boys, her predilection pulled hopelessly between rich and poor, slyness and goodwill, possessiveness and levity, tall-dark-and-handsome and a zest for life, etc. Failed thespian and broke ex-boyfriend John (Chris Evans), and magnate gentleman crush Harry (Pedro Pascal) are, inexplicably, never pitted against each other. When one seemed about to take up a conversation with the other in a bar, the film cuts to the next scene. As the self-centred Millennial matchmaker Lucy, Dakota Johnson is the sole emotional centre this film has.

Song’s desperation for artsiness is what stifles the little spontaneity she’s got. Her writing and staging leans towards the uninspired, almost priggish, kind of urbane, and she throws her homiletic weight around what should’ve been a frivolous pleasure. She talks of Jane Austen and Nora Ephron in interviews, but her sensibility is too sanitised and understated — too Asian (and Canadian?) — to give the film the charge of When Harry Met Sally… (1989) or Pride & Prejudice (2005)

There’s the Lubitschian set-up — Harry sits Lucy down ostensibly for some lectures on matchmaking, at a wedding she arranged for his brother, where John also happened to be as a waiter — but no tension follows from it, because the situations are so underplayed for naturalism that either there’s no interesting turn in a dynamic that much of the picture is stuffed in unrewarding slack, or when there is, there’s no zing to it; the moment when Coke and beer were served before they’re even ordered was probably one of many intended jokes, and it never came off.

Even the casting of the triangle follows a very quaint Asian logic of putting together the most conventionally alluring people alive. Yet there is something to be said about pairing Johnson with Pascal and Evans as her two suitors. They had never been that impressive as actors go (barring Pascal). What they do have is the bearing and physiognomy of a star; the pictures come to life in their presence, even when their performances falter. It’s reported that Song wanted to subvert the genre tropes with insights straight from the modern dating scene. From the look of it, the result is an abject failure: all the genre trappings are still there, and the message never gets very far beyond “As a creature of publicity and commodity fetishism, dating has taken away the risk and spontaneous pleasure of love, made it needlessly complicated, and people turn themselves into insatiable losers for it.” But taking a step back, you might ask: what truths could you possibly be spouting with three bodies perfectly made for an effeminate fantasy? (Who even believes Evans in the part of a working-class cavalier?)

Past Lives had a tormented undercurrent that flew under Greta Lee and Teo Yoo’s every exchange of harmless ideas, and you don’t feel the same sense of self-conflict brewing within Johnson, the last person you go to for psychological nuance. Song miscalculated where her temperament ends and where Johnson’s persona begins. A line like “I’ll take it to my grave” obviously doesn’t play into Johnson’s type, so it’s not at all surprising when it was dropped like a stilted dud. She’s often muffled in a way that’s not of a piece with Song’s kind of restraint.

Dakota Johnson is not the kind of actor that has the measure to transform a director’s vision, yet she brings to her awkwardness and amorphousness a lulling charm that few better actors can (“ambien-haze,” I’ve seen it called); she’s a God-bless in an inane nothing of a movie like Am I OK? (2022), and you wish nothing in the world steals that charm away from her. Much as their roles were underwritten, she’s in her better elements here because she has Pascal’s regal manliness and Evans’ semi-Romeo glamour to play off. Dashing in strapless navy blue, she’s fatuous in a way that both enchants us and limits our response. Lord only knows what a filmmaker like Megan Park, who loves their actors and who knows their range and limits, and what they’d bring to an ad-lib, can do with someone like her. If her part here has no more dimensions than Irene Dunne’s or Margaret Sullavan’s, or more recently Sydney Sweeney’s or Adria Arjona’s, we know there’d be no point in settling for more. Her very image should be a sign not to hold Materialists to any high standard.

Song has yet to grow out of the playwright and has already made classic mistakes of a filmmaker, despite all her visual flourishes with Shabier Kirchner the cinematographer. Her dialogue constantly throws you off balance by spelling out the most obvious, which is the definition of a playwright’s crime. It isn’t hard to read some camp into these line deliveries that make you want to guffaw in the highest register, because the unbelievably serene people that inhabit this silly romance give it the contour of a starry-eyed girl’s fever dream. Pascal has never been glibber than his courtly-to-the-end “What if I’m incapable of it? Love?” The worst mistakes are Song’s as a filmmaker.

There are reasonably endearing scenes: the foreplay between a dumbfounded Lucy and a suave Harry that stretches miles across from the door to the bed in Harry’s mansion-sized apartment; John’s hand-held “broke men propaganda” in which he takes it out on his lousy roommate and a bathroom mirror door that never closes properly in their cramped apartment. There was never a firm grasp of structure, however, and without it, Song’s dramaturgy falls apart. At every turn, when the drama seemed about to thicken or turn a new corner, it merely fell back on its own feet. Even the latest of Justin Baldoni or Will Gluck was more than happy to exploit the most obvious potentials in their material. When a twist does come, it’s the stalest trick in the “kitsch” book, like the date of a favourite client (Zoë Winters) gone horribly wrong just when Lucy was on the precipice of success, or a life-changing blemish that dwarfs an otherwise perfect loverboy, or when, after a kiss, an ex-boyfriend suddenly throws a non-tantrum over whether Lucy is serious about him.

The expositions are pretty much all that the themes have going for them, but since they’re not that deep anyway, you’re not too bothered by all the underdeveloped ideas that “could’ve been.” The plot progression, motivations, and some of the lines walk such an uneasy line between synthetic escapist fantasy and “responsible” messag — manufacturing that they don’t make a whole lot of sense, but you wonder if it’s all the worse for it. I wish Song had taken her time to settle for a unified tone and played her hands with a more well-rounded triangle, and she needs more confidence to develop as a dramatic/comedic writer. On the whole, Materialists is nothing to be ashamed of (except a needless prologue set in the Stone Age). It has the special ambience and feeling that only belongs in a romance, and that isn’t something anyone can bring off even with all the “right” elements. I sat there smiling at the screen, at the sensuous faces and figures, at the mistimings, at the silliness and artifice, against all my better judgments. And I kept smiling.

USA • FINLAND | 2025 | 117 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Cast & Crew

writer & director: Celine Song.

starring: Dakota Johnson, Chris Evans, Pedro Pascal, Zoë Winters, Marin Ireland, Dasha Nekrasova, Louisa Jacobson, Sawyer Spielberg, Eddie Cahill, Joseph Lee, John Magaro (voice) & Baby Rose.

Originally published at https://www.framerated.co.uk on June 21, 2025. All images are used according to the Fair Use doctrine in US & UK law for review, commentary, and education.