Dark City (1998) • Limited Edition 4K Ultra HD [Arrow Video] — a beautifully baffling genre-bending mystery

A man struggles with memories of a past he doesn’t recognise, which includes a wife he doesn’t remember having, and a nightmarish world where nobody can wake up.

A Gothic-noir-science-fiction-psychological-crime-drama, with profound subtext? As is so often the case with films that bravely weld together different genres, creating a fresh fusion, confounded distributors and audiences alike back in 1998. It’s one of the most misunderstood movies of the 1990s. But there were some, including a handful of perceptive critics, who recognised it as one of the most original productions of that decade, and it’s been building a devout cult following ever since. Now, with a 4K restoration of the much sought after 2008 Director’s Cut released on a double-disc box set loaded with new extras from Arrow Video, we can enjoy Dark City as intended and the high definition means we get to see new details in the gloom.

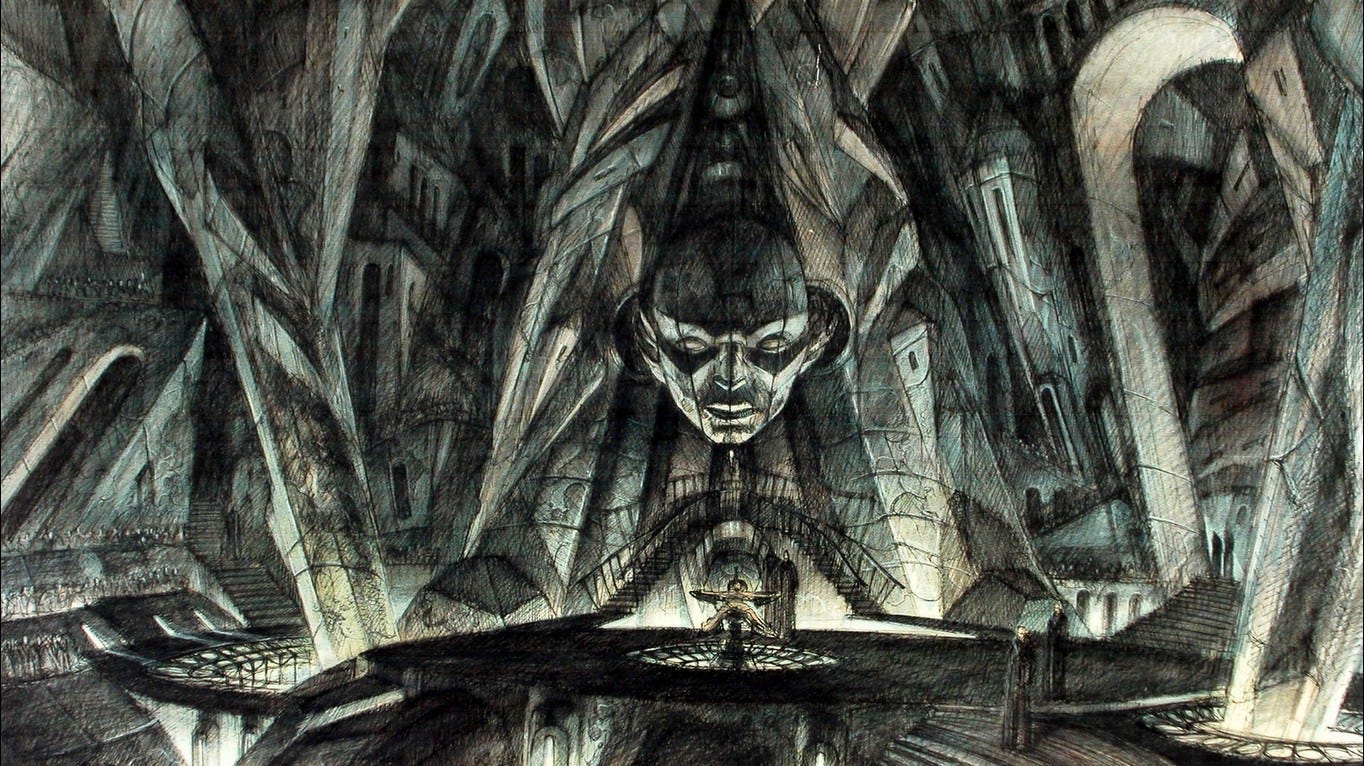

Dark City has been justly compared to Blade Runner (1982) and surely drew visual inspiration from common sources including classics of German expressionist cinema such as Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and, most obviously, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927). Like Blade Runner, its setting is a gloomy urban labyrinth of deep dark streets, where it seems to be permanently nighttime — but by contrast, and rather conspicuously, it never rains in this dark city. Both films tackle the same philosophical questions: are we merely the sum of our memories? If we lose our memory, do we lose our self, or is there another intrinsic component that makes us who we are?

As with many movies that ask their audiences to think, test screenings for Dark City didn’t go very well. Audiences were baffled by the enigmatic first act and lost interest before answers started to arrive. So, just as with Blade Runner, the executives at New Line Cinema insisted that a voiceover was added to make things clearer and a montage sequence lay things out more explicitly. So, in the opening minutes, the voice of Dr Daniel P Schreber (Kiefer Sutherland) tells us, straight-up, all about the ‘Strangers’ and pretty much spoils all the surprises to come. Thankfully, that’s now been fixed with the definitive Director’s Cut that expands the opening scenes and, if anything, add to the enticing enigma. Instead of telling, director Alex Proyas shows us plenty of clues in a succession of not-so-subtle metaphors that come thick and fast in the first 10-minutes.

Although Dark City would certainly appeal to the Blade Runner crowd, for me, a more significant cinematic precursor, in mood and narrative style, would be Angel Heart (1987) which, incidentally, also has a richly resonant score by Trevor Jones that really helps envelope the viewer in a moody, almost stifling atmosphere. Both explore shifting identity and the correlation between memories and the human soul and take stylistic cues from noir detective movies. They also have central characters called ‘Johnny’, who seem to be followed by a trail of murders that implicate them, though Dark City certainly turns out to be the more optimistic of the two.

We first meet J. Murdoch (Rufus Sewell) as he stumbles naked from a bath and practically trips over the carved-up corpse of a woman. He seems completely confused and disorientated, and we soon learn that he has no recollection of who the murder victim is, how he came to be in the same apartment, or indeed who he is! He only knows his name from a business card he finds and has no idea what his first name is apart from the initial ‘J’. Dr Schreber telephones the mysterious apartment and tells Murdoch about an experiment that went wrong and resulted in the erasure of his memory before stoking his panic with the paranoia inducing warning that there are people coming for him as we speak and urging him to leave the murder scene immediately. There’s some extra material in the Director’s Cut here, involving the changing identity of the concierge which were excised for being either too subtle to be noticed at all, or too confusing for those who did notice.

Thinking quickly, he flees. On the way through the hotel lobby the concierge tells him that he left his wallet at a neighbourhood diner the previous night and best retrieve it so he can pay his overdue rent. Disposing of his suitcase and anything that could link him to the crime scene, throwing it all into a nearby canal he wanders the unfamiliar night streets looking for the diner. The information in the wallet is a mismatch to the personal effects he just got rid of. So, the stage is set for a delicious whodunnit mystery, with a great shock reveal to come now that that pesky opening narration has been removed.

Speaking of stages and sets, the entire world of Dark City was purpose-built as one huge, self-contained sound stage which features alongside some meticulous miniature work and VFX under the guidance of Peter Doyle, adding a magically unreal atmosphere. In his debut feature The Crow (1994), writer-director Alex Proyas had tested the idea of a large set, made to look even bigger by rearranging walls and rooftops between shots. Here, he takes it to a whole new level with what was, by far, the biggest set ever constructed in Australia. The detailed production design overseen by George Liddle and Patrick Tatopoulos, mixes together different eras. Unusually for science fiction it draws mainly from the past, with classic cars and 1940s styles conjuring the timeless atmosphere found in the ‘Americana paintings’ of Edward Hopper and classic film noir.

With careful lighting, along with a seamless marriage of mechanical and digital effects, cinematographer Dariusz Wolski evokes an effectively immersive atmosphere. Like Proyas, he’d cut his teeth on music videos (for the likes of Suzanne Vega, Tom Petty, and The Bangles) and had already proved himself in cinema with Romeo is Bleeding (1993). He has since gone on to the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, and his more recent work can be appreciated in The Martian (2015), Alien: Covenant (2017) and Napoleon (2023). He’d worked with Proyas on The Crow and the legacy of their shared background in promo videos can be seen throughout Dark City. With an average shot length of around two seconds, it remains one of the most rapidly cut narrative films and demands a high level of visual literacy from audiences. However, the Director’s Cut also restores several interactions that do slow things down a bit, but in a welcome way that really builds mood and benefits the pacing as it fills out a few characters that had previously seemed to be little more than cyphers.

By 1990, Proyas had been doing very well directing pop videos for MTV and felt ready to make his move into feature films. He’d already written a script for Dark City and began touting it around Hollywood, to no avail. Everyone who glanced at it found it far too confusing, but producer Ed Pressman recognised enough potential to offer him The Crow. He proved to be the perfect choice, and his adaptation of the cult comic-book was soon receiving favourable reviews and breaking through to the mainstream. The Crow was enough of a hit to spawn several sequels, but Proyas wanted to move on and make something original. After the success of The Crow, he found people were more willing to take a chance on his ambitious Dark City screenplay.

Proyas was clearly inspired by the Nova trilogy of novels by William S. Burroughs, particularly The Ticket that Exploded, first published in 1962, which is set within a revolving and shifting constructed world, where trapdoors and chutes connect numerous false realities and time zones. Humans and aliens are manipulated by the Nova Mob, an extra-terrestrial gang, using any-and-all means available to them including drugs, hypnosis, surgery, and language to destroy entire cultures. It’s a Burroughs story, so who can really say what’s going on, but its sense of deep paranoia and identity crisis is effectively evoked in Dark City. As is the reality shifting delirium when environments slide and morph into somewhere different. No doubt the Wachowskis had this imagery in mind as they were writing their screenplay for The Matrix (1999), which borrows heavily in aesthetic terms from Dark City along with some thematic overlaps.

There is also a marked parallel between Dr Schreber and the character of Doc Benway, who recurs in many Burroughs novels. The name, Daniel P. Schreber, is directly lifted from a real psychiatric case that had been of great interest to Burroughs, as well as to the father of modern psychology, Dr Sigmund Freud, and became one of the earliest documented cases of what we now call paranoid schizophrenia.

Apparently, his first draft was even more Burroughsesque, but Proyas admitted it was a tad too dark and confusing. So, he brought in Lem Dobbs to develop it for the screen. Dobbs had just written Kafka (1991), which explains why the final version is also very Kafkaesque. Let me tell you, Burroughs plus Kafka is a heady mix! In his treatment, there was still much mystery and only when the film’s cast was confirmed, pulling in a larger budget, was David S. Goyer brought in as the third writer.

Goyer introduced most of the VFX-laden action sequences, which have since been criticised as incongruous. Those critics do have a point, but the sequences are necessary to fully tell the story and bring more mainstream appeal to what could easily have been a sombre arthouse film. Having said that, it’s the spectacular climax in which Murdoch does psychic battle with the Strangers that most dates the production and invites closer comparison with The Matrix.

The obvious visual and conceptual similarities between Dark City and The Matrix have been widely acknowledged. Interestingly, Andrew Mason, was a producer on both and, according to Proyas, the Wachowskis attended a screening of Dark City in the summer of 1997, well before they began filming The Matrix. So, it’s reasonable to assume the similarities between these two films aren’t purely coincidental.

It’s no wonder the cast engendered confidence with investors. Rufus Sewell, may not have been A-list at the time, but he’s thoroughly compelling in a rather complex and multi-layered lead role, which is lucky as we spend most of our screen time with him. He’s joined by Jennifer Connelly (Labyrinth) as Emma, who’s purportedly Murdoch’s wife. Always captivating, Connelly was already a genre fan-favourite and earning a reputation as a versatile actress. Here she plays a deeply emotional role with admirable restraint and subtlety, three years before the industry would applaud her with a string of accolades including an Academy Award, a BAFTA, and a Golden Globe, for her part in A Beautiful Mind (2001). The late William Hurt (Altered States) seems to have taken cues from her and is also engrossingly understated as Police Inspector Frank Bumstead — he can convey so much with a simple sidelong glance. Then we have Kiefer Sutherland playing Dr Schreber with ingenious ambiguity until he gradually veers towards the heroic.

We know we’re in safe hands with Ian Richardson as the arch-villain, Mr Book. He relishes the role and his Shakespearean background shines through. And although Richard O’Brien may not have the same reputation or classical stature as an actor, he’s superb as Mr Hand, one of the Strangers imprinted with the mind of a murderer to more effectively track down Murdoch. Apparently, Proyas wrote the part with him in mind from the start.

When not disguised in their long coats, dark suits, and hats, the cadaverous Strangers seem to have been taking fashion tips from the Cenobites of Hellraiser (1987). They also have a neat line in levitation and it seems their spiritual cousins made a special appearance in Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s “Hush”. It’s one of the scariest and most respected episodes and features similarly bloodless men, also wearing dark suits and carrying Gladstone bags, who levitate and drift through Sunnydale’s silent streets at night.

Dark City certainly exerted a significant influence that still ripples through genre filmmaking. It was very ambitious — a huge production in every respect, except budget, delivering great value for money at well under half the cost of The Matrix the following year. American uber-critic Roger Ebert hailed it as the best film of 1998, later hosted a scene-by-scene appreciation at a festival, and then contributed an audio commentary for an earlier DVD release of the Director’s Cut. Ebert’s praise wasn’t much help at the box office, where it performed rather poorly in the wake of James Cameron’s world-conquering Titanic (1997), only narrowly clawing back its $27M budget.

Proyas took a break from Los Angeles for a while and stayed in Australia to make coming-of-age comedy drama Garage Days (2002). He bounced back with another film exploring what it means to be human — an adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s story I, Robot (2004), starring Will Smith and a budget five times that of Dark City! Although it was a box office hit, it seems that the Hollywood machine had lost some of its lustre for Proyas, who decided to continue his career in Australia where he made Knowing (2009). That sci-fi mystery starring Nicolas Cage received mixed reviews but was also a success, hitting the №1 spot in several territories.

Proyas was born in Egypt but his family emigrated to Australia when he was a small boy, so with Gods of Egypt (2016) he wanted to connect to his ancestral roots, but despite some Ray Harryhausen-esque Sinbad-style fun the movie was decried by most critics and caused controversy with a predominantly white cast playing Egyptian characters. It struggled to recoup its $140M budget during its theatrical release. Perhaps I shouldn’t admit this, but I rather enjoyed Gods of Egypt — albeit after a few cocktails! Regardless, Alex Proyas can console himself that Dark City remains a ground-breaking cult classic and he was able to reconstruct his original vision. I must say that although the theatrical release was impressive and has remained a favourite, I had to admit there were a few flaws. I’m elated to say that the new Director’s Cut has fixed them all. It’s well worth revisiting.

USA • AUSTRALIA | 1998 | 100 MINUTES (THEATRICAL) • 112 MINUTES (DIRECTOR’S CUT) | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

2-Disc Limited Edition 4K Ultra HD Special Features:

Brand new 4K restoration from the original 35mm camera negatives approved by director of photography Dariusz Wolski, who has ensured excellent dynamics that really show-off the production design and, almost, seamlessly matches the restored footage into the Director’s Cut.

4K Ultra HD (2160p) Blu-ray presentations of both the Director’s Cut and Theatrical Cut of the film showcasing this literally dark movie like never before. Except for reasons of nostalgia and comparison, the Theatrical version is effectively redundant but completists still need to have it in this pristine edition.

Original DTS-HD MA 5.1, stereo 2.0 and new Dolby Atmos audio options for both cuts of the film, which gives suitable emphasis to the score by Trevor Jones and sound design by a team headed by Lisa Bate and Gareth Vanderhope.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing.

60-page perfect bound collectors book featuring new writing by author Richard Kadrey, and film critics Sabina Stent, Virat Nehru and Martyn Pedler. Not available at time of review.

Limited Edition packaging featuring newly commissioned artwork by Doug John Miller.

Double-sided fold-out poster featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Doug John Miller.

Three postcard-sized reproduction art cards.

Postcard from Shell Beach and Dr Schreber business card, which are both small though super-cool artefacts.

Disc 1 — Director’s Cut

NEW audio commentary by director Alex Proyas.

NEW audio commentary with Craig Anderson, Bruce Isaacs and Herschel Isaacs, co-hosts of the Film Versus Film podcast, giving a fan perspective and sharing their extensive knowledge and hindsight.

Three archive audio commentaries: by director Alex Proyas, film critic Roger Ebert, and by writers Lem Dobbs and David S. Goyer — all lending their individual perspective. Although they inevitably cover much of the same ground, there are valuable nuggets to be found in each that will delight dedicated fans of the film who are happy to hear a lot of the same things repeated.

Archive introduction by Alex Proyas and Roger Ebert.

‘Return to Dark City’, NEW hour-long documentary featuring interviews with director Alex Proyas, producer Andrew Mason, production designers Patrick Tatopoulos and George Liddle, costume designer Liz Keough, storyboard artist Peter Pound, director of photography Dariusz Wolski, actor Rufus Sewell, hair & makeup artist Leslie Vanderwalt and VFX creative director Peter Doyle. Covering the making-of Dark City from initial concepts and rough drafts to rewrites and pitching to production companies. Then discussing the development, starting with Disney, then moving to Fox and finally entering production with New Line Productions. I particularly enjoyed the section involving the writers as they talked about process, concept, and characters. Proyas provides plenty of detail about the 65-day shoot that wasn’t enough. The near failure of the film ever coming to fruition and the extra fortnight he was granted to pull it all together. There’s also some unguarded comments on the tension between the writers and the studio executives reaching the conclusion that the bigger the budget, the small and safer the ideas must be. The ideas explored in Dark City are neither small nor safe. This is all very informative and worthwhile, though does become a little repetitive at times.

‘Rats in a Maze’, NEW 14-minute visual essay by film scholar Alexandra West in which the research work of Edward C. Tolman involving the cognitive mapping of rats challenged with changing mazes is discussed with reference to the city environs in general and Dr Schreber in particular, who is indeed shown observing rats in a large dramatically underlit maze.

‘I’m as Much in the Dark as You Are’, NEW 20-minute visual essay by film scholar Josh Nelson on film noir and identity in Dark City in which he applies some astute analysis while compiling quotes form theorists about what makes a noir beyond the obvious visual stylings. This can be summed up as a narrative that usually revolves around a stranger entering a hostile world in which they must fight to survive, and ultimately change.

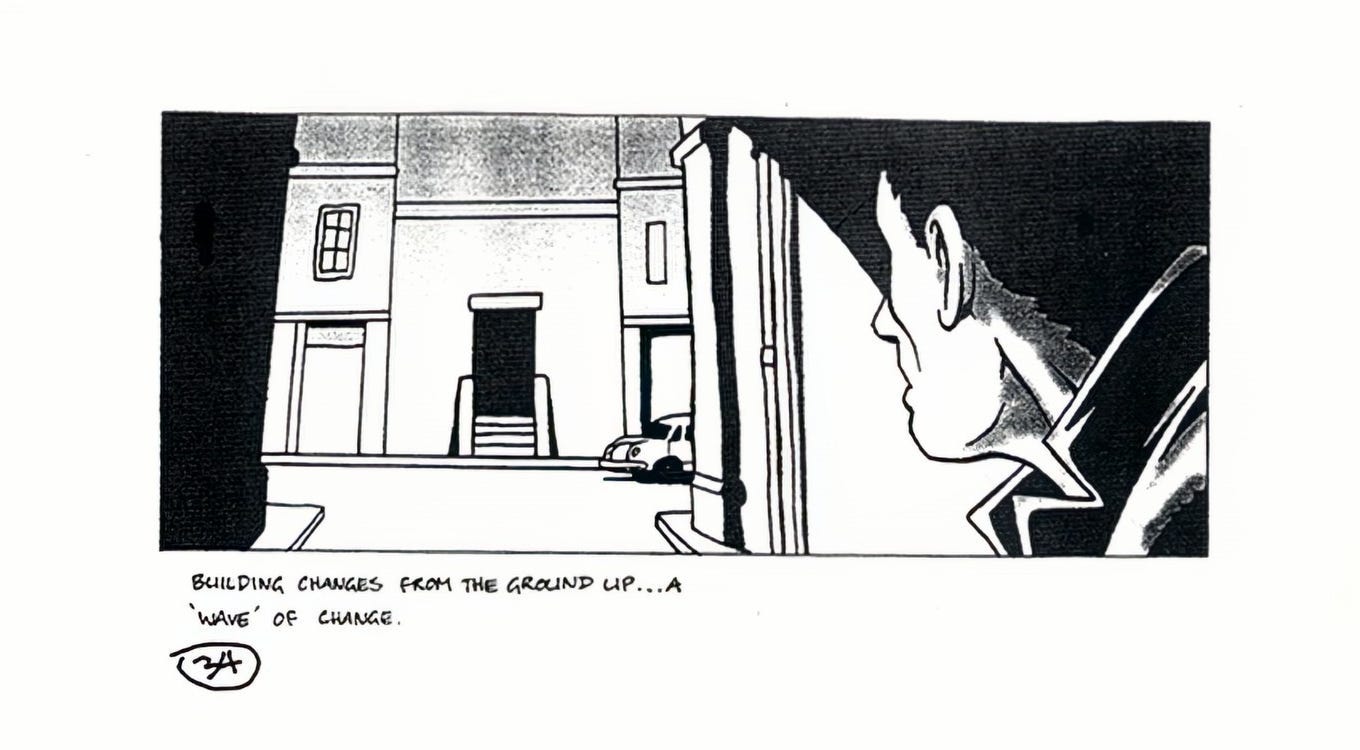

Design & Storyboards. A real highlight of the release with plenty of lovely concept art and a detailed run though the storyboard, or sections of it at least…

Disc 2 — Theatrical Cut

Archive audio commentary by director Alex Proyas, writers Lem Dobbs & David S. Goyer, director of photography Dariusz Wolski and production designer Patrick Tatopoulos. Who better to provide a thorough commentary on the creative and technical aspects of the movie. Again, we hear a lot of the same information and anecdotes already covered in the commentaries and interviews on Disc 1.

Archive audio commentary by film critic Roger Ebert. A fair critic and an enthusiastic fan.

‘Memories of Shell Beach’, a 33-minute featurette from 2008 in which cast and crew look back at the making of the film from concept to reception. Interesting but much of the information, along with many of the anecdotes and quotes, is repeated in the very similar Return to Dark City documentary on Disc 1.

‘Architecture of Dreams’, a short 33-minute featurette from 2008 presenting five perspectives on the themes and meanings of the film. Film critics and scholars go deep with analysis and opinion.

Theatrical trailer.

Image gallery.

Cast & Crew

director: Alex Proyas

writers: Alex Proyas, Lem Dobbs & David S. Goyer (story by Alex Proyas).

starring: Rufus Sewell, William Hurt, Kiefer Sutherland, Jennifer Connolly, Richard O’Brien, Ian Richardson, Bruce Spence, Colin Friels, John Bluthal, Mitchell Butel & Mellisa George.

Originally published at https://www.framerated.co.uk on June 21, 2025. All images are used according to the Fair Use doctrine in US & UK law for review, commentary, and education.

¹ This article contains Amazon affiliate links, which earn us a tiny commission to help maintain Frame Rated if you use one to make a purchase — at no extra cost to you.